Mind and Body: Nurturing the Child

"The damage that happens to kids from the infectious disease of toxic stress is as severe as the damage from meningitis or polio or pertussis."

Dr. Tina Hahn, pediatrician, Caro, Michigan

- More than 1 in 4 U.S. kids experience a serious traumatic event by the age of 16, including abuse, neglect and household or neighbourhood violence, according to the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

- More than 1 in 5 children have experienced at least two of these traumas and are more likely than others to have school difficulties, along with health and behavioural problems, a 2014 study found.

- Nearly half of U.S. children younger than 18 live in families at or near the poverty level, U.S. Census data show.

- The number of U.S. children in foster care climbed steadily after 2011, reaching nearly 430,000 in 2015, the most recent government data show. Neglect was the reason in nearly two-thirds of cases, with most of the rest due to drug abuse, according to a 2016 government report. Authorities believe the opioid epidemic has contributed to the trend. CBC News

|

| Safe spaces, quiet times and breathing exercises for preschoolers are designed to help kids cope with intense stress so they can learn. (Chuck Burton/Associated Press) |

Pediatricians in the United States were urged by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2012 to make an effort to convince parents of young children along with the public that the long-term consequences of toxic stress does long-term harm of both physical and psychological values to children exposed to situations and circumstances that create an insecure and fearful environment for them in their most formative years.

The push was on to call for new public policies and possible treatments geared at preventing or reducing the effects of stress in vulnerable child populations. Recent studies' outcomes appear to validate that the stress children suffer with lack of adequate nurturing, changes the body's metabolism, contributing to internal inflammation, potentially raising the risk of developing diabetes and heart disease.

Researchers at Brown University in 2015 reported findings of elevated levels of inflammatory markers in the saliva of children who had experienced some manner of adversity, including abuse. Animal study experiments suggest that persistent stress may have the capacity to alter brain structure where emotions and the regulation of behaviour is concerned.

"We know that if they don't feel safe then they can't learn", commented mental health specialist Laura Martin, of children who have experienced the treadmill of going in and out of foster homes, or the strained life they experience alongside parents struggling with drug and alcohol dependencies, supplemented by poverty, depression, and domestic violence. When they arrive at school they are unfocused and withdrawn.

This leads to social behaviours that become a problem the schools find they must deal with. Children who kick and scream at their classmates and their teachers. Aggressive discipline has been placed high on a shelf as a response that hasn't worked well in the past. Instead, methods whereby the children's insecurities can be addressed are attempted, in an effort to lead them away from the stress their normal lives burden them with.

At school, children in these programs called "trauma-informed" care, based on research pointing to potential biological dangers of toxic stress leading to a new approach for public health to identify and treat the effects of poverty, neglect, abuse and allied adversities, are leading the way. At home these children "never know what's going to come next", while at school there is quiet time and regularized routines, breathing exercises, and other aids to help angry children deal with conflicts.

Behind these new experimental teaching techniques is the acknowledged science that the brain and disease-fighting immune system, not yet fully formed at birth, remain vulnerable to damage from childhood adversity, according to studies, with the first three years the most critical. Children without nurturing parents or in the absence of other close relatives to step in to help cope with adversity are recognized as being most at risk.

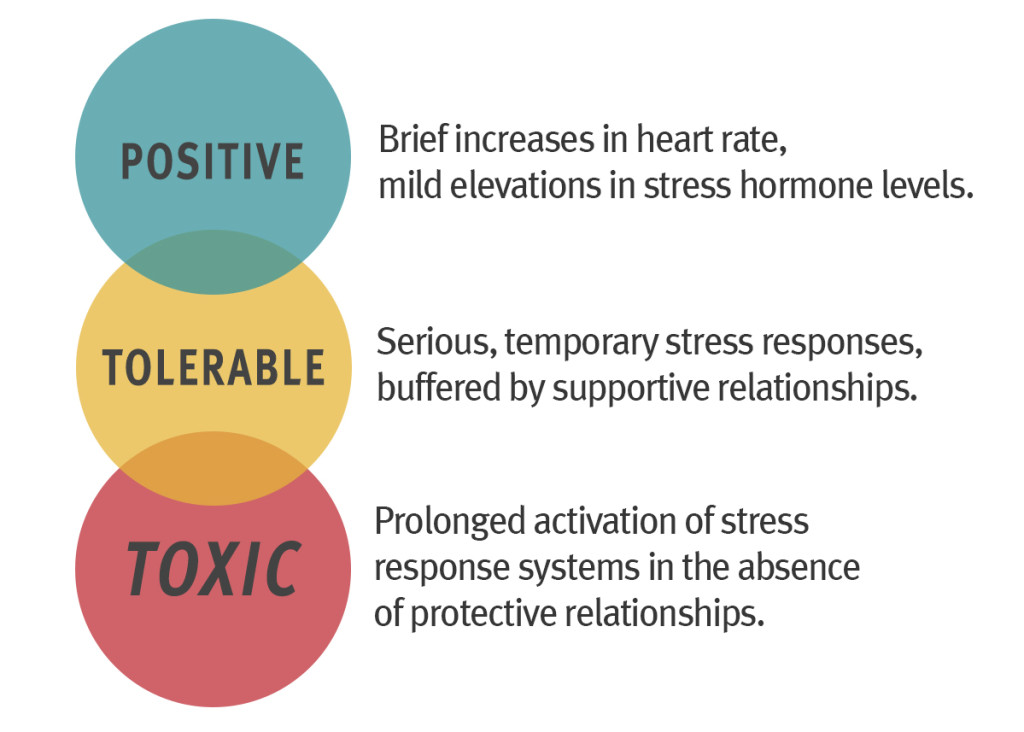

Harvard University neuroscientist Charles Nelson explains that under normal stress conditions the response kicks in briefly to raise heart rate and levels of cortisol and allied stress hormones. But when that stress is severe and remains ongoing, the levels of stress have the potential to remain elevated, placing children in a persistent state of "fight or flight". Imaging studies show regions in the brain affecting emotions and behaviour tend to be smaller than normal in children who have suffered severe trauma.

Research carried out on neglected children in Romanian orphanages lead to the suggestion that early intervention may lead to a reversal of damage from toxic stress, so that orphans placed in the care of nurturing foster families before age two produced imaging scans years later demonstrating that their brains appeared similar to those of children never institutionalized. Whereas those children in foster care at a later age had diminished grey matter, their brains appearing similar to those of children remaining in orphanages.

"The science of how poverty actually gets under kids' skin and impacts a child has really been exploding", explained a former president of the American Academy of Pediatrics. The landmark U.S. government-linked research, called the Adverse Childhood Experiences study published in 1998 led the way to this later research, finding that adults exposed to neglect, poverty, violence, substance abuse, parents' mental illness and other domestic dysfunction were likelier than others to experience heart problems, diabetes, depression and asthma.

Adults with six or more such adverse childhood experiences in their early background died an average of twenty years earlier than those with no such adverse experiences, according to a follow-up study conducted in 2009.

Labels: Bioscience, Child Welfare, Diabetes, Health, Heart Disease, Research

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home